A sense of humor and just enough gall to win

Following is the text of 1995 Scholar Ryan Sneed's address

at the Byrnes Foundation fortieth annual luncheon, June 14, 2003.

When Kristine Hobbs asked me at Super Weekend to speak on James F.

Byrnes today, I was completely blown away by such a request. Of all

people, how was I going to be able to speak about a man I had never

met, and my only relationship with him was through books, newspaper

clippings, and the occasional anecdote by those who knew him.

My introduction to James F. Byrnes began like many of us; I received

a scholarship from the James F. Byrnes Foundation. I had little knowledge

of who this man was and what he accomplished in his political career.

As a senior in college, I had to do a thesis, which was confined to

the years of 1920 and 1945. Without hesitating, I decided to explore

the life of James F. Byrnes during those years. So, after many red

inked drafts, "James F. Byrnes, Roosevelt's 'Assistant' President

from 1942-1945" was born. This was my first formal introduction

to who this man really was and what he accomplished.

Now that I've been out of college a while, I thought surely you would

never see me again in a library, especially doing any sort of research.

But as I began to delve into the life of James F. Byrnes, once again,

I found that I had really missed some things the first time around.

I had missed out on his charm, his love for serving people, and his

sense of humor.

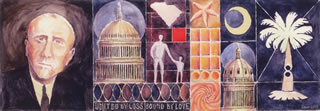

James Francis Byrnes was know by many titles: He was known as Representative

Byrnes. Senator Byrnes. The Honorable James F. Byrnes. Justice Byrnes.

Assistant President Byrnes. Secretary of State. The Great Compromiser.

The Jaunty Irishman. Governor Byrnes. Jimmy. Jim, to close friends.

Or even Pop to some.

He wore many hats and held many titles, however he never lost sight

of his humble beginnings. During his 1950 campaign for the 1951 gubernatorial

Election, a reporter asked Byrnes, after he had addressed an auditorium

of grade-school students and talked with many of them, if he minded

being informally addressed as "Jimmy" by the youngsters.

Byrnes replied, "Certainly not. Because when a youngster calls

me 'Jimmy,' I know I have their daddy's vote."

But before he held all those titles, Byrnes began his life under humble

circumstances at 128 Calhoun Street in Charleston, SC.

Byrnes was born May 2, 1882. He was the grandson of Irish Catholic

immigrants who came to American after the Great Irish Potato Famine

in the 1840's, and the Byrnes' family originally began life as immigrant

farmers on the Yamasee River in lower South Carolina. He was the son

of James Francis Byrnes, who died two months before his son's birth

of tuberculosis, and Elizabeth McSweeney Byrnes. Because of his father's

untimely death and his mother working tirelessly as a dressmaker, Byrnes

left school at the age of 14 to help support his family. When I say

family, I mean it in every sense of the word. In the Byrnes' household,

in addition to raising her son and daughter, the young widowed Mrs.

Byrnes supported her invalid mother, her sister, and her sister's son.

Byrnes always said that his family motto was, "Eat it all, wear

it out, make it do."

Byrnes' mother taught him shorthand, which was useful after he left

school, as he soon got a job at a law office in Charleston as an errand

boy. Little did anyone know that this would be the launching ground

for what was to become his political career.

Although Byrnes didn't officially finish school, later in life he

was honored by many honorary degrees from colleges such as: Columbia,

Yale, Pennsylvania, Washington and Lee, UNC, Clemson, College of Charleston,

Presbyterian College, The Citadel, Furman, Wofford, and the University

of South Carolina. Later in life, Byrnes quipped, "I could not

afford a formal education, but now in my old age, I'm educated by degrees." Byrnes'

career began almost in a whirlwind. After he was admitted to the South

Carolina Bar Association in 1903, he purchased the Aiken Journal

and Review newspaper which he edited weekly until he was elected

as the Solicitor for the Second Circuit in 1908. He was elected to

the US House of Representatives in 1911 where he served for 14 years

until 1925. Recalling his first campaign, Byrnes said, "I campaigned

on nothing but gall, and gall won by exactly 57 votes."

But even after Byrnes had left his small town newspaper in Aiken,

South Carolina, the editor in him still prevailed. After arriving in

Washington, Byrnes noticed that the Washington railroad station had

misspelled Spartanburg by adding an extra 's' making it Spartansburg.

True to his early editing practices he wrote the railroad station telling

them, "you need to learn how to spell."

In 1925 Byrnes turned his attention to the US Senate, however, Byrnes

lost in a close election. But true to one of Byrnes' favorite adages, "winners

never quit, and quitters never win," he sought the seat again

in 1930 and won in a landslide victory. He served in that capacity

unit 1941 when he was appointed to the United States Supreme Court.

This prestigious appointment was in part due to his loyalty to President

Roosevelt and Roosevelt's "new deal" platform.

Byrnes only served on the Supreme Court for sixteen months. Normally,

a Supreme Court appointment is a lifetime appointment. Byrnes, however,

under his own free will stepped down from what he thought would be

his most prestigious role in his political career.

Because on the morning of December 7, 1941, the Japanese attacked

Pearl Harbor, thrusting the United States into World War II. And on

the morning of December 8, President Roosevelt summoned Byrnes and

Byrnes offered up his services immediately to Roosevelt. Byrnes would

prove himself indispensable to Roosevelt and the war effort, earning

the unofficial title of "assistant president." Byrnes' job

was to run the home front while Roosevelt was tending to the issues

of the war. However, when Roosevelt would run into a snag and needed

votes, he would send out his number one politician to sway the votes

in his favor.

Byrnes rarely ever spoke on the floor because he preferred a more

private environment. This was usually done in what many of the politicians

referred to as Byrnes' "Cloakroom." This was nothing more

than a janitor's closet that had been transformed into a small office

for Byrnes, resting perfectly off the House and Senate corridors. Byrnes

would pull individual Senators and Representatives aside as they were

leaving sessions and invite them into his "cloak room" to

what Byrnes termed as "to strike a blow for liberty," which

in layman's terms means nothing more than to drink down a couple of

stiff bourbon drinks. The cloakroom had nothing more than a card table,

a couple of folding chairs, a liter of Hankey Bannister Bourbon, and

a bottle of branch water with a couple of antique glasses. This was

where Byrnes was at his best. Turner Catledge, a journalist during

those times wrote, "Byrnes was a born manipulator, he could con

the pants off of anyone in Washington."

Byrnes served as Roosevelt's right hand man through the war in the

capacities of Director of War Mobilization and Director of Economic

Stabilization, which respectively prepared the country for war and

then capped the inflation of goods and salaries and implemented rationing

of high demand resources.

Byrnes was not used to the media frenzy that he encountered after

being appointed Director of War Mobilization. His first press conference

took place in the White House's "Fish Room," which had mounted

fish all over the walls. Noting one particular fish, Byrnes' first

statement to the press was, "I feel like that fish. I'm sure if

he had a sign right now it would say, if I had kept my mouth shut,

I wouldn't be here on this wall."

While serving as Director or War Mobilization, Byrnes was instrumental

in the "Manhattan Project," which lead to the development

of the Atomic Bomb. Later in the war, he was integral in making the

decision to drop the bomb.

After the war, Byrnes traded in his domestic policies to become an

indispensable American diplomat as Secretary of State under President

Harry S. Truman. Byrnes was instrumental in concocting some of the

Cold War policies that would influence politics well into the 1980's.

After Byrnes left his position as Secretary of State, he returned

to South Carolina and rumors began to circulate that Byrnes would run

for governor, and he did just that. Byrnes served as Governor of South

Carolina from 1951 to 1955. This was the last political office Byrnes

held.

Byrnes' life truly surrounded what he stated as, "The highest

of distinctions is service to others." And to capture his life

of public service, Byrnes began work on his memoirs, which resulted

in his first book, Speaking Frankly, and later, All In

One Lifetime. With the proceeds from these books, the James F.

Byrnes Foundation was born and the first scholarship was given in 1949

in the amount of $500. After receiving royalties from his first book

in the amount of $20,000, Byrnes stated, "This was the only real

amount of money I ever had."

But of all the accomplishments in Byrnes' life, his most prized accomplishment

was marrying Maude Busch of Aiken, South Carolina. Mrs. Byrnes was

a beautiful and talented recent graduate of Converse College, an institution

that was noted for turning out what Byrnes said were "superior

and gracious ladies." They married on May 2, 1906, ironically,

Byrnes' birthday. However, they married under some controversy. Maude

being an Episcopalian, and Byrnes being baptized Roman Catholic, posed

a problem for the couple getting married in the small town of Aiken.

But to satiate the church's stance on the subject, Byrnes begrudgingly "converted" to

the Episcopalian faith. On commenting on his faith in his book, All

in One Lifetime, Byrnes wrote, "For myself, I think a man's

religion is a matter between God and himself and I dislike the hypocrite

who parades his religious views no less than the bigot who arouses

prejudice against other faiths." However, no matter with which

denomination Byrnes' allegiance laid, he was always steadfast in his

Christian beliefs.

Byrnes's Christian beliefs carried over into every aspect of his life,

as he never told nor cared to hear a profane story. Byrnes was a great

storyteller, however. He loved to tell and hear a good story. One of

his favorite stories was that of the time that he picked up two hitchhikers

outside of Bethesda, Maryland. Byrnes recalled:

I was hailed by a young sailor, who asked for a ride for himself

and his redheaded buddy, who was leaning against a telephone pole.

When I agreed to take them into town, the sailor at the pole started

navigating toward the automobile and I knew the telephone post had

performed a useful service. The smaller of the two sat next to me.

The inebriated redhead also got into the front seat and put his head

back in comfortable relaxation. The little, but talkative, one seemed

afraid I might object to the condition of his friend and tried to

keep me diverted. He asked what kind of work I did. I said, "Right

now I'm out of a job." He seemed sympathetic and asked what

my job was when I worked. I said, "I was Director of War Mobilization." His

expression clearly showed he had never heard of it. After being quiet

for a second or two, he made another effort, "Well, what did

you do before that?" "I was the Economic Stabilizer," I

said. He had never heard of that one either. "I mean before

the war," he replied. "I was a Justice of the Supreme Court," I

told him, thinking that that at least would impress him. He asked, "You

mean the highest court?" "Yes," I said. With his elbow

he nudged the other boy asking, "How would you like to be a

member of the highest court?" Shaking his head the intoxicated

redheaded slurred, "I wouldn't like it. There's no chance for

a promotion."

Fortunately, James F. Byrnes never viewed any position he held as

having no room for promotion. He always proved himself indispensable

to his country, his friends, his wife, and his children, which is how

he and Mrs. Byrnes referred to the scholars of the Byrnes Foundation.

Even after he retired from his life in politics, he still made himself

available to politicians who asked for his advice. One politician that

sought out his services regularly was President Richard Nixon.

President Richard Nixon wrote these words after Byrnes' death on

April 9, 1972: "James F. Byrnes was one of those men who ranked

principles first and that should be his legacy to all of us who seek

to serve our country. No man in American history has held so many positions

of responsibility in all branches of our government with such distinction.

He was a great patriot who always put his country ahead of his party."

President Nixon ordered that flags across the nation be flown at

half mast in honor of Byrnes. Nixon's statement may have summed up

Byrnes' political career. However, the courage, character, personality,

and vision that made James Francis Byrnes began with a mother's love,

grit, and determination. And with just enough gall to win by 57 votes

he embarked on an illustrious political career that propelled him from

the House, to the Senate, to the White House, and to the halls of the

United Nations. And all Byrnes said he ever wanted out of politics

was "three meals a day, two new suits a year and a reasonable

amount of good liquor." He may have left his mark in this world

through his political career, but his legacy lives on here today through

who he and Mrs. Byrnes referred to as their "children."