A Close Friend Remembers ‘Pop’ Byrnes

Following is the text of Walter Brown's keynote address at the Byrnes Scholars 21st annual luncheon, June 4, 1984.

It is a real pleasure for me to be with you today, as it has been on many previous occasions. As I recall I provided, at least by car to the Byrnes’ home on Woodburn Road, the speaker for the first meeting of Byrnes Foundation students (1949). He was a great scholar and educator in his time, Dr. Henry Nelson Snyder, who for many years was president of Wofford campus.

Dr. Snyder made this comment: “It is difficult for me to realize that Jimmy Byrnes, who has been a man of modest income most of his life, would now give away the first money of any consequence he has ever made to educate boys and girls who are struggling as he did in his youth in Charleston to get an education.”

That said something to me I had not fully appreciated and something I trust Byrnes Scholars will always remember.

I enjoyed a close association and friendship with Mr. Byrnes for over 40 years. In thinking what I should talk about today, I concluded you would be interested most in my telling some of the highlights of this long association and giving you a little history to take home with you.

Let me first tell you briefly about his early life in Charleston to which Dr. Snyder referred. Mr. Byrnes’ rise from his humble beginning to a national and world figure reads like a Horatio Alger story. He was born after his father died. His mother, Elizabeth E. Byrnes, was an expert seamstress and to provide for her two children and Frank Hogan, her sister’s son in Washington who was confronted with a similar hardship, she made dresses and did sewing for the more fortunate families in Charleston. Leonore, Jimmy and Frank Hogan, who later became a distinguished and wealthy Washington lawyer, were brought up under Mrs. Byrnes’ guidance and her doctrine of “clean your plate, wear it out and make it do.” When Jimmy became old enough to work, he sensed that he needed to help his mother with expenses and secured a job as a messenger in a Charleston law firm. Subsequently, he read law under Judge Benjamin H. Rutledge, who was a great help to him in securing a non-college education. He knew firsthand the need of children whose home had been touched by parental death.

I did not know Mr. Byrnes until he came to the Senate in March 1931. How we first met is an interesting story in itself. I was in the Capitol press gallery at the time, representing Carolina newspapers. Soon after he was sworn in, President Hoover declared a moratorium on foreign debts. I decided that the South Carolina freshman senator, who had served in the House for 12 years, would be worth a good interview on this subject, and I went to his office in the old Senate Office Building. When I opened the door leading to the reception room, the only one there was a sparsely built man in his shirt sleeves beating an Underwood #5 typewriter with more speed than I had ever been able to attain on a similar machine in my National Press Building office. I asked the person at the typewriter to see Senator Byrnes and received the short, cryptic reply – “Who are you and what do you want to see the Senator about?”

I rose up with all my recently found dignity as a Washington correspondent and with some resentment told this person, who I thought was just an office stenographer, the names of the South Carolina papers I represented and that I wanted to talk to his boss about the Hoover moratorium. Seeing, my agitation, the man at the typewriter gave me a friendly Irish smile and replied, “I am Senator Byrnes.” He saw my great embarrassment but quickly put me at ease by giving me an interview that made the headlines in my papers. That was over 50 years ago, but this incident has been etched in my memory ever since. From that day on, a friendship began that grew and developed over our entire lives in Washington and continued in South Carolina until he left us here in Columbia in 1972 at the age of 92.

Recently in Atlanta I heard a Sunday sermon in which the minister made this statement, “Oh, God, what a fantastic time to be alive!” That was how Mr. Byrnes felt; and although a workaholic, he enjoyed life to the fullest. He lived by that passage in Timothy: “For we brought nothing into this world and it is certain we can carry nothing out.”

Mr. Byrnes was instrumental, along with Donald Russell and the late Greenville publisher, Roger Peace, in convincing me to give up my newspaper career in Washington and become a South Carolina Broadcaster. I will never forget him telling me not to be solely interested in making money. He said, “Walter, don’t ever try to make more than $25,000 a year. That’s all the money anyone ever needs to enjoy life.” (Of course, that would be over $100,000 today.)

I’ve heard him say many times that all he wanted in life was a new suit of clothes a year, three meals a day and a reasonable amount of good bourbon.

When he told me that he had been recommended for a place on the United States Supreme Court and decided to accept that appointment, I was one of the few who urged him not to leave the Senate. He was to me an “All American Senator”, and I did not think he would enjoy the cloistered life on the Supreme Court.

It was not long after I had been at the White House for his taking the oath as Associate Justice that I visited him at his Isle of Palms home near Charleston. When I walked in, he was in a front room overlooking the ocean which he had set up as his workshop. There he was working on three big stacks of petitions for writs of certiorari and sweating like a plow hand. When I greeted him, he said, “Walter, you might have been right about urging me not to take this job on the Supreme Court.” Then he said, “Let’s strike a blow for liberty” and soon Mrs. Byrnes joined us with the bourbon old fashioned and small low country river shrimp he enjoyed so much.

I have ever known a better conversationalist. He was one of the few persons in high places I have met who was just as good a listener as a talker. Also, he was a man with tremendous sympathy for anyone who was going through a sad experience. Mr. Byrnes carefully read all obituaries in the South Carolina daily newspapers. When he came across the notice of death of one he knew quite well, he would either call or write a letter of sympathy to the family.

Mr. Byrnes never liked to listen to dirty or sex stories. In fact, he would often turn away when one was being told at a party. He had a keen and wonderful sense of humor: he would tolerate no vulgarity. He never used profanity, and about the strongest language I ever heard him use was, “That beats hell’s room.”

When I read today of the tremendous sums of money, running into millions of dollars, that Senators now spend to get elected, I think of Mr. Byrnes’ 1936 campaign for reelection to the Senate. I was with him in his office in Spartanburg after he had become an important cog in the New Deal and many Washington lobbyists wanted to make a campaign contribution for his reelection hoping to gain some favor. I saw him returning these checks with a nice thank-you letter. One such check was from Joe Kennedy, then a part of the Roosevelt administration and who lived to see one of his sons elected President. Mr. Byrnes told me he was not going to accept any contribution from any lobbyist or anyone in government who could call on him for special favors.

I remember another story he told me when he was with the President in the White House soon after Mr. Roosevelt took office. The President was going through his mail and came across a letter from one of Mr. Byrnes’ colleagues in the Senate. The president picked up the letter and handed it to his secretary, and said, “Missy, put that letter in the file of Unsolicited Advice.” Whereupon Mr. Brynes said, “Mr. President, I do not know how long you will be President or how long I will be in the Senate, but I can tell you one thing – you will never find a letter from me in that file.” Mr. Byrnes, throughout life, was short on giving anyone unsolicited advice.

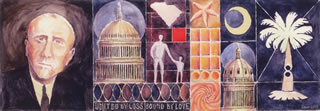

Now let me turn to something that concerns me and other living friends of Mr. Byrnes. I refer to the fact he had not yet received due credit for his great public service in all three branches of the federal government and as Governor of South Carolina.

Unfortunately, after he became Governor and, to some extent, after his Washington and Lee address which led to the break with President Truman, Mr. Byrnes was falsely pictured by the national media. He was painted as bitter and eaten up with jealousy by not being selected by President Roosevelt as his running mate in 1944 and not being friendly to the blacks because of the educational program he sponsored as Governor.

Nothing could be further from the truth. If any man ever had reason to be bitter and disappointed, Mr. Byrnes had that right, but he was not that kind of individual.

Of course, when Mr. Byrnes was Governor, there was a wide gap between educational facilities in the rural and urban areas. As a Justice on the Supreme Court, he knew that unless South Carolina complied with the then separate-but-equal Constitutional doctrine, public schools in this state and the South would be in serious trouble. Under his leadership, the General Assembly enacted the one-cent sales tax for education, and the records will show that most of it went for improving black schools.

I will not go into the long fight waged so eloquently by John W. Davis, the great Constitutional lawyer who was the Democratic nominee for President in 1924 and my friend, Robert Figg, former dean of the University of South Carolina Law School and a confidant of Mr. Byrnes. What they and the other distinguished lawyers were trying to do, more or less, under the Governor’s auspices, was to keep control of the public schools in the states and local school boards as they believed the Constitution provided. That as it may be, the national media used this to picture Mr. Byrnes as harboring ill will to the blacks.

Now, much has been written about what happened to Mr. Byrnes at the 1944 Democratic convention that nominated President Roosevelt for a fourth term, but I believe you would be interested in what happened at the 1940 convention when the two-term precedent was broken and Mr. Roosevelt was nominated for a third term. I was at both conventions. My newspaper reports as to what happened at the 1940 convention vary quite a bit from Mr. Byrnes’ recollection in his second book, All in One Lifetime. I wrote it on the scene and as it occurred.

At President Roosevelt’s request, Senator Byrnes handled the platform and third-term nomination. He did a masterful job in the face of the opposition from Vice President Jack Garner, Postmaster General Jim Farley, Governor Al Smith and many others.

After Mr. Roosevelt was nominated, Mr. Byrnes met with party leaders the next morning at the Blackstone Hotel. The question to be decided was who would be the Vice Presidential nominee. While the conference was going on in the Blackstone, a call came in to Mr. Byrnes from the White House. He took it in the bathroom adjoining the conference suite. It was Mr. Roosevelt on the line.

He first told him what a fine job he had done in carrying out his wishes with the platform committee and handling his third-term nomination. He then again assured him he was his choice as his Vice Presidential running mate but began reporting conversations he had with Archbishop Francis Joseph Spelman of New York and some big city party bosses. As the President was reciting these conversations to the effect, as the Vice Presidential nominee, he would hurt the ticket because of his leaving the Catholic Church early in life and his opposition to the anti-lynching bill in the Senate, which Mr. Roosevelt himself never supported, Mr. Byrnes interrupted him. In no uncertain terms he told the President to forget what he had told him about being his choice for Vice President.

He said in effect, “Mr. President, I was the victim of this kind of talk when I first ran for Senate in 1924. If I thought your choosing me as your running mate would cost you the Presidency when I feel you should stay in the White House for a third term when your leadership is so badly needed because of the world situation, and tell me who you want on the ticket.”

When the President said it appeared to him that Secretary of Agriculture Henry Wallace was the best choice, Mr. Byrnes returned to the party leaders’ conference in the next room and proceeded to put the machinery in order to carry out Mr. Roosevelt’s wishes.

Mr. Byrnes left that conference and came to my room across the street at the Stevens Hotel (now the Hilton), where I had been closeted for days, at his request, working on his acceptance speech for Vice President. He broke the news to me by repeating in detail his bathroom conversation with the President. He saw I was upset and asked me to accompany him in his special car to the convention hall. On the way out, we continued our discussion. I detected he, too, was somewhat upset at the turn of events but, in some way, relieved.

Neither of us expected the pandemonium that was taking place against Wallace when we arrived at the convention. Mr. Byrnes had to go from delegation to delegation, telling them the President would not accept his third-term nomination unless he had Wallace on the ticket.

When Senator Carter Glass and other Senators went to the White House the following January after the 1940 election to urge Mr. Roosevelt to nominate Mr. Byrnes to the Supreme Court, he did not hesitate to tell the Senators he would do so and went further to say ‘Jimmy’ was his choice for Vice President, but religion and racial issues had been raised, but they would not have amounted to anything.

I regret to say Mr. Roosevelt was not so frank and considerate at the 1944 convention after Mr. Byrnes left the Supreme Court to serve him as Assistance President in the White House after Pearl Harbor. The President again passed him over as his fourth-term running mate even after more definite assurances were given than in 1940.

After the 1940 convention Mr. Byrnes continued as Assistant President in the White House and made a most effective nationwide radio speech in behalf of Mr. Roosevelt’s reelection for a fourth term. At the President’s request, he accompanied Mr. Roosevelt to the Yalta Conference, which was the last one of the “Big Three”. This was shortly before Mr. Roosevelt’s death at Warm Springs.

Vice President Truman knew in detail the story of the 1944 convention and the role he was to play by nominating Mr. Byrnes for Vice President. They had been close friends in the Senate, and Mr. Byrnes stood by him politically and financially when the President sought to defeat him in the 1938 Missouri Democratic primary with Governor Lloyd Stark, the apple grower.

I have always felt Mr. Byrnes’ resignation as Secretary of State could have been avoided, as well as the bitterness that followed, had it not been for the “Palace Guard” around the President in the White House and some people in the State Department. It should be remembered that, as Secretary of State, Mr. Byrnes spent over half of his time out of the country attending foreign conferences and their friendship eroded when Mr. Byrnes could not go across the street at “Bull Bat” time and, over a bourbon and water, discuss what had transpired that day.

The power of the White House to influence the media and public opinion is always great, but it was especially that way after Mr. Truman’s unexpected victory over Tom Dewey in 1948. Certainly, those around the President lost no opportunity to picture Mr. Byrnes in a bad light. Thus, Mr. Byrnes’ contribution to his state, nation and the world during his lifetime continues to be grossly ignored by the present-day writers and historians.

I have no doubt, in time, when the true history of the Roosevelt-Truman era is written, James F. Byrnes will emerge as one of the great statesmen of his time and will be ranked with John C. Calhoun and the other great men South Carolina has produced.

Let me again thank you for the opportunity to be with you today. I wish you every success in your life’s endeavors because, as Byrnes Scholars, you carry a great name – one of which you can ever be proud of.